Chimora’s Nomuntu Kapa is a voice that once defined an era.

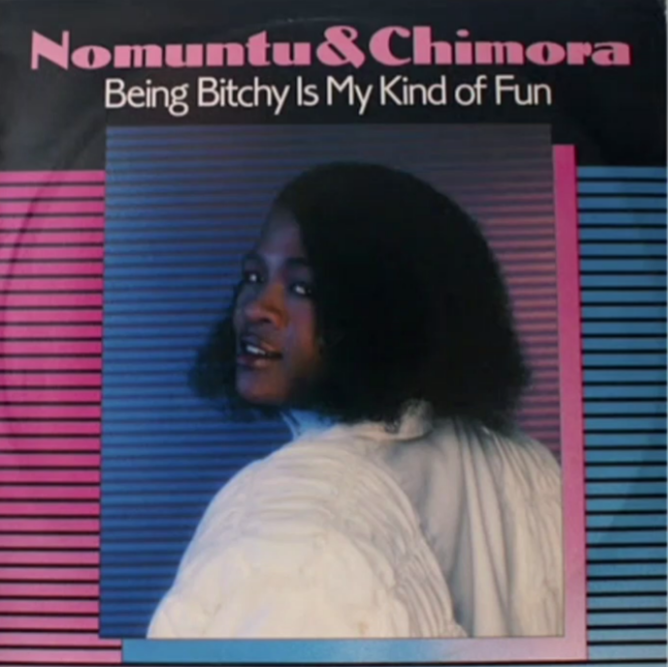

The band is remembered for timeless hits such as Bad Boys, Daddy’s Dead, Being Bitchy is My Kind of Fun, and Save Me, songs that lit up dancefloors, echoed on radios, and became the soundtrack of the 80s.

Her powerful voice and bold presence made her one of the most unforgettable figures in South African music.

But behind the rhythm and the applause was a story of betrayal, exploitation, and survival. While her songs soared to double platinum success, Nomuntu was left without royalties, battling depression, and struggling to make ends meet. The music that once brought her joy became a painful reminder of dreams stolen and promises never fulfilled.

In this hard-hitting and painful exclusive interview with Africa Jamz FM News, Nomuntu finally breaks her silence — opening up about the glory, the heartbreak, and the lessons she hopes today’s young artists will take from her journey.

How her music journey began

Nomuntu begins by sharing how her journey in music first started.

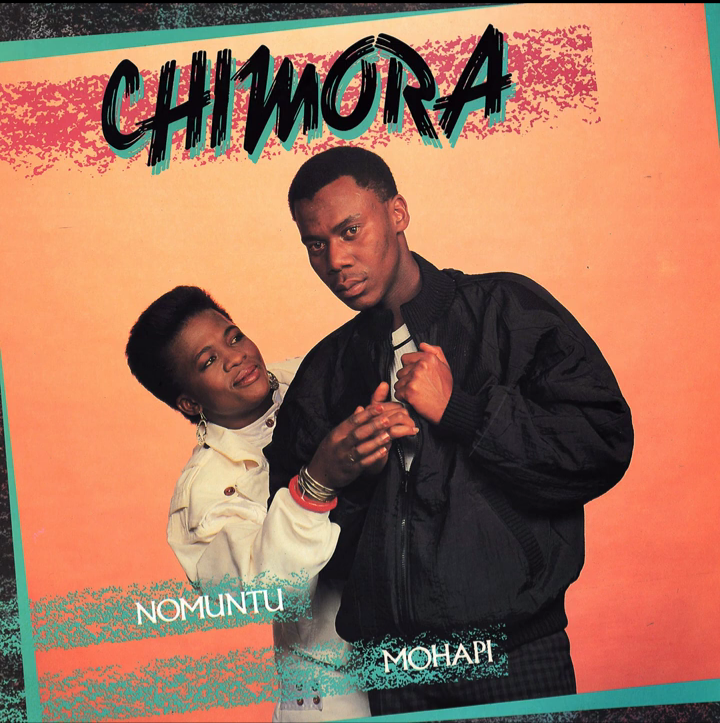

“My music journey began long before I became the first member of Chimora, collaborating with Mohapi Mashego under the production of Chicco Sello Thwala. Back then, during the apartheid era, I was already performing as a cabaret singer in hotels and nightclubs. Later, I moved to Johannesburg with Sizwe Zako as part of Pure Magic, performing in stadiums and at festivals. That’s where I met and worked with many music legends, including Stimela. I was their curtain-raiser and backup singer for about a year, until they left for the Graceland Tour with Paul Simon,” said Nomuntu.

Fame without fortune

As she continues her story, Nomuntu begins to explain how things started unfolding differently from what she had anticipated.

“Then came Brenda Fassie. She approached me to work with her in the studio on the album Umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu. After that, I met Chicco Sello Thwala, who produced my first album as part of Chimora in 1987, alongside Mohapi Mashego.

That album featured songs like Bad Boys and Daddy’s Dead, and it went double platinum. But despite its success, I was only paid R12,000. The album was under Gallo Records, directed by Phil Holls. I wasn’t even informed when the album won an award—I heard from a friend. Still to this day, I do not know who received this award on my behalf. I received no royalties from SAMRO, even though I was a registered member. I gave up chasing my money and ended up falling into depression. It broke me, but I held onto hope.

“I continued performing at indoor shows and festivals, always to full houses. Yet, I was paid only R150 per show by Baphom Company. My music was everywhere—on radio, on TV—but my family back in the Eastern Cape thought I was wealthy because I was famous. They didn’t know I was being exploited. I was given contracts to sign without being allowed to take them home or consult a lawyer. As someone who came from Bantu Education, I didn’t understand the confusing clauses. I kept recording with them, even though I was unhappy, because they said my contract wasn’t finished,” said Nomuntu.

From bad to worse

While Nomuntu speaks openly about being robbed and exploited, her story doesn’t stop there—in fact, things only got worse. She goes on to reveal even more of her heartbreaking journey:

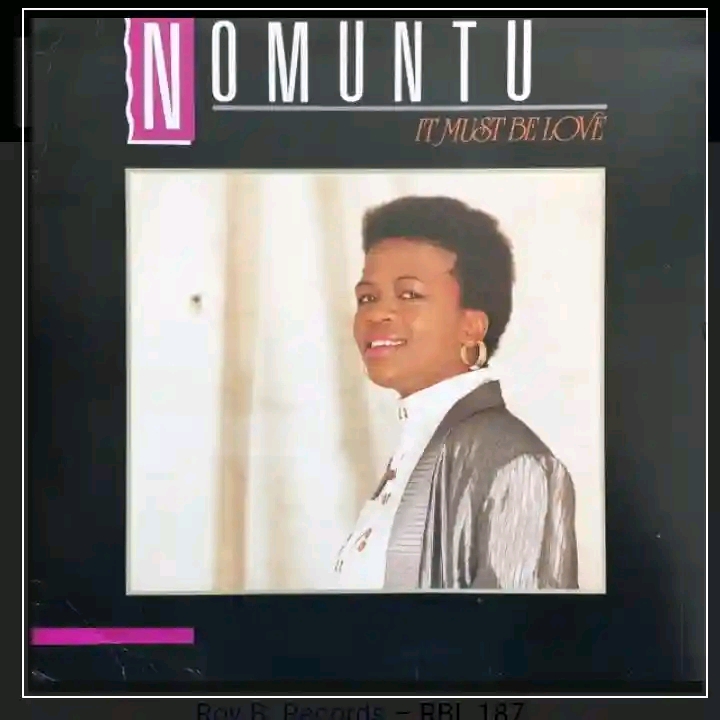

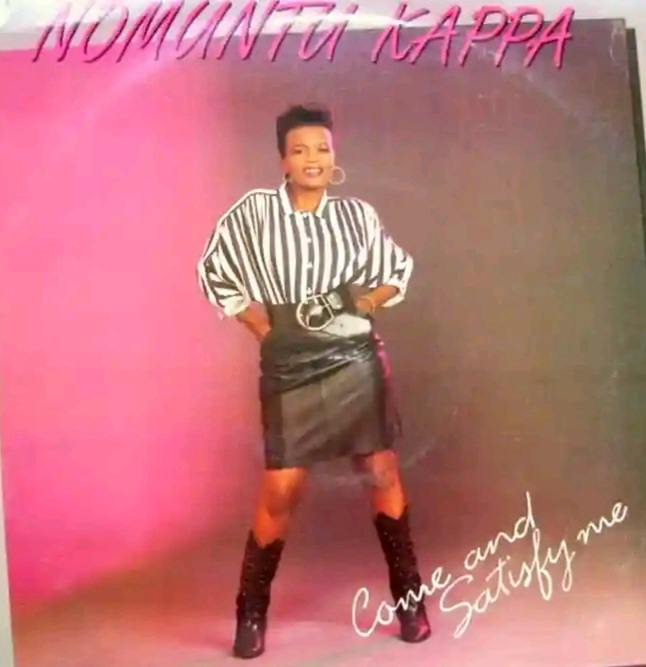

“In 1990, I recorded my third album Cone and Satisfy Me with Thapelo Kgatho of Stimela, followed by It Must Be Love. Same story again—I would be given a cassette with backing tracks, write my own lyrics and melodies at home, but when the album came out, I wasn’t credited as the songwriter or composer. Instead, names of people I had never met were listed. I asked questions, but no one gave me answers. My albums weren’t even available in local record stores. I later found out they were being sold overseas. My daughter in England confirmed this. Still, I received no royalties.

“In 2019, I registered with IMPRA for needle time and received R1,417.04. But later, they told me Chicco had taken Chimora’s contract to SAMPRA. I had registered as an individual artist under the name Nomuntu. SAMPRA told me I needed a clearance from IMPRA to get paid. I did everything they asked, but I’m still waiting. Today, I survive on an old-age pension. The money I made in music is long gone, and the companies that exploited me have disappeared. I live on borrowed property, struggling to make ends meet,” said Nomuntu.

Lessons learned

As Nomuntu wraps up her moving story, she reveals the emotions she’s grappling with, how her music—which once filled her with happiness—now causes her pain, and the important lessons she hopes younger generations will learn from her mistakes.

“It’s heartbreaking to hear my music playing and see people look at me, thinking I’m living well. As we speak, I do not own property and find myself a tenant at my old age. People have downloaded my music without permission. What used to bring me joy now makes me sick. I’d rather listen to someone else’s music than my own. I hope young artists learn from my story. I should never have trusted blindly or signed anything without legal advice. I was naïve. I should have insisted on having a lawyer review my contracts,” said Nomuntu.

HAVE YOU CHECKED THIS OUT: Nandi Nyembe dies a legend, not a beneficiary: FOSA demands royalties for SA’s forgotten actors

[…] HAVE YOU CHECKED THIS OUT: Chimora’s Nomuntu Kapa breaks silence on music, exploitation and survival […]